Body Honesty

How this era’s art is debunking body shamers.

How this era’s art is debunking body shamers.

With armpit hair censored on Instagram, Gigi Hadid called ‘too big’ for modeling and period adds being banned for ‘inappropriateness’, it appears that for us women, there is no place left for anything less than ‘perfection’ in this society. Being aware that beauty ideals go back to an untraceable time, it is safe to say we have reached the limit. As we are the Selfie obsessed, social media horny generation with a strong opinion and a reasonably big ego, it seems the fingers are all pointed at us; and so we left ourselves with a mess, where deviations of what we consider perfect are selectively disregarded and 80 per cent of the female population feels awkward about themselves. Isn’t it time for us to fight this weird situation we have found ourselves in before we lose the idea of what the reality actually is? Being bored of the traditional female body parading throughout the art scene, these next artists challenge the idea of beauty and provide us with a brutally honest representation of female diversity.

Exploring the struggles of ‘black’ hair through pastel coloured still lives, Nayeka Brown might be the perfect badass example of self-acceptance. Confronting us with the reality of our definition of beauty in the context of a black woman, the photographer dares to tackle the taboos surrounding body image, race and tradition in an undeviating way.

If there is one thing to admire this Finnish artist for, it’s her courage to approach her body in a humorous way. Shoving a broom under her boobs, putting on a hat with ‘bread hair’ while standing on a treadmill, nothing is too absurd for this upcoming photographer. However while she’s having the time of her life making these shots, she’s simultaneously teaching the world a lesson about body shaming, taking a piss with beauty ideals and questioning the fact that abnormal may be normal.

Although still finishing up her studies, illustrator Layla May Ehsan is already getting her voice out there, and I can assure you it is a powerful one. Highlighting a painful and these days rather shaming thing that goes on inside women’s bodies, Layla’s period drawings are aimed to start a conversation, pointing out the ridiculousness of the lengths the world goes to in order to avoid the ‘gross’ subject of menstruation.

As tolerance is hiding behind a world full of stereotypes and discriminating thoughts, there is a powerful counter reaction going on to actively help our society towards acceptance. From indie films dedicated to a love for chubbiness to a photography movement capturing body reality of our diverse society, it seems we are finally ready to be honest about our bodies and if body honesty is the theme of this era’s art, than at least there is something we are doing right.

ANDROGYNY: An inherent truth?

What can we learn from androgyny? The artist challenging gender fluid stereotypes and promoting a different kind of well-being: Nastasia Niedinger

What can we learn from androgyny? The artist challenging gender fluid stereotypes and promoting a different kind of well-being: Nastasia Niedinger

Nastasia Niedinger is a unique product of the millennial age. A contemporary creative on the outside looking in, she is a hungry observer and spokesperson for those equally curious about the modern human condition into which they were born. Fascinated by post-modern and generational trends, she utilises art direction to produce remarkable pieces with profound social messaging. Her primary mediums include writing, photography and experimentation with digital spheres, which she uses to highlight incumbent cultural mechanisms at play. Always aiming to help viewers understand better the world around them, Niedinger’s attitude seems ever forward-looking.

Universal androgyny. The concept may seem peculiar, but one photographic study suggests just that. Gender in Utero is an intimate study of androgyny with a strong ideological underbelly. Tired of just the “what?” and determined to ask “why?”, this collection and its critical rhetoric is bucking trends in the media’s recent coverage of gender fluidity - and in more ways than one.

Gender in Utero is unique in its duality, making clever use of art to support social commentary. The collection uses photography as a medium to document the phenomenon in its physical form: the artist iterates our physical inheritances - the appearances of both mother and father - and although this is often taken for granted, she has found it to be a profound and inspiring truth.

But the message at its core is the prevalence of androgyny in our behaviour and observed benefits for the psyche. The artist asks viewers to consider, “How do I feel? How do I think?”, encouraging them to evaluate the fluidity of their own behaviours and thoughts.

“I believe androgyny is not only natural but inherent. It occurs moment by moment, case by case, in each of us. Faced with a multitude of situations, we unconsciously flex between feminine or masculine behaviour.

Androgyny is tantamount to people’s ability to evaluate, objectivise, empathise, subjectivise, and so on.”

The project’s title, “Gender in Utero”, pays homage to the unique development of the human mind and advancement over time. “A component of human nature is our inherent adaptability, in the short and long-term.” And though Nastasia observes that action is constantly changing, more fundamental still is the understanding that consciousness itself is after all, genderless.

Its poignant insights are supported by classical writer Virginia Woolf and pioneering psychologist in creativity and “flow states”, M. Csikszentmihalyi, whose research claims, “A psychologically androgynous person in effect doubles his or her repertoire of responses.”

Execution of the collection has abided by strict principles, sourcing participants from outside of the modelling industry and rejecting androgyny as a means for fashion, which Nastasia claims to be constraining. “Often, designers encourage diversity for the sake of diversity, freedom for the sake of freedom, without explaining its value.” Examples include Selfridges’ recent Agender floor, which although publicised gender as a construct, for all its PR failed to explore the implications of the statement. The artist holds a critical outlook on the subject, stating that:

“Androgyny has been commodified by fashion, and hijacked by sex. Neither industry is exploring why aesthetic or sexual liberation does good for the well being - areas like self esteem, flexibility, and of course empathy”.

Gender in Utero was born out of a firmly collaborative effort between Nastasia, photographer Al Overdrive and makeup artist Sophie Yeff. The trio have utilised an acute sensitivity to human physiology to produce a gripping standard of portraiture. Its founders mark an expanding community, coordinating a larger production team to cater for its growing number of subjects.

These captivating pieces and rhetoric are a refreshing departure from ineffectual “gender fluid” posturing in the media, (many gaining views using provocative but unanswered questions). Instead, the project demonstrates the potential inclusiveness of androgyny, inviting individuals to celebrate the benefits of fluid thinking in everyday life. Gender in Utero boldly addresses the big “whys” which industries like fashion and sex overlook, and gives those who identify with the “genderless mind” a powerful visual means to reclaim androgyny.

Want to explore more? Interact here www.genderinutero.com

Sex in the art scene

How art is demolishing the misconceptions around sex and sexuality (and why this is a good thing).

SEX, SEX, SEX. Next to eating and sleeping it’s one of the most mundane and self-evident phenomenons in our human lives, however with constituted social norms telling us to oppress our sexuality and discard any exceptions on the ‘normal’ conceptions, thus treating it as a taboo subject, I bet that somehow some of you still feel the embarrassment creeping into your body when reading those three first words out loud in the office or during a family dinner.

Living in 2015, there is still so much wrong with the misconceptions formed around this broad subject. Yet luckily for us there is an active movement going on in the creative scene and the polished and one-sided approach we’re used to is gradually being substituted by an honest representation changing our narrow perspective on what sexuality really entails.

Describing themselves as a liberation from a culture of self-hate and impossible ideals, Ladybeard fights the reinforcement of a demeaning attitude towards sexuality. When we were all too busy flashing our boobs on the Internet with the hashtag #freethenipple hoping for a change, the team behind Ladybeard made an entire magazine!!! accessing real sexual experiences and voicing sexual diversity.

© Shan Huq SS16 - Photography Thomas McCarty - via dazedigital.com

Shan Huq

“These clothes are the essentials of your wardrobe, but also the essentials of your mind, the essentials of life and the essentials of your sexuality”. New to the fashion scene and already making statements, Shan Huq’s creations represent the reality of young Americans, tackling sexual taboos in a brilliantly cheeky way. Subtly touching the taboo subjects: gender, beauty and sex, the brand pushes the straightforward boundaries which the fashion industry continues to occupy.

Ren Hang

Having been arrested for “suspicion of sex”, Chinese photographer Ren Hang has experienced right handed how much of a taboo sexuality continues to be in this modern age. Yet instead of being discouraged by the extreme consequences of his work, Ren does not let this get in the way of his creative process. Showcasing the naked bodies of his friends in its purest form, he manages to capture images that go beyond the focus on sex, making them both arousing and scenically interesting at the same time.

To the people that think our generation of artists is deconstructing everything that has been built up for the last hundreds of years, I say so what. It was about time. Our society is in need for individuals like the ones above, so we can leave all those misconceptions about sex and sexuality behind us and work towards that one moment where we can finally all openly accept that women do masturbate, there is no one in this world that is 100 per cent straight, and sex is as opposed to what you have been watching in your bedroom with the door locked, more raw and real than anything you have ever been confronted with on the internet, rap song video clips or perfume adds.

Making art about food waste: Interview with artist Louiza Hamidi

For Louiza Hamidi, it is our conceptual exploration that reclaims moments as art. And she likes to make art about food waste.

For Louiza Hamidi, it is our conceptual exploration that reclaims moments as art. And she likes to make art about food waste.

I met Louiza Hamidi a few years ago when we studied together for our fine art degree, we have remained friends and collaborated on many works to varying degrees. Louiza and I collaborate on our pop up installation Food Waste Café, where we cook and serve food waste to visitors in a restaurant setting, but Louiza has been very busy with food waste since her degree. She has embarked on a food waste tour of England, exploring how food waste is managed in other cities, she has completed a half marathon fuelled by food waste and she has invested a great deal of time into collecting food waste from supermarkets and distributing it through Curb, an active food waste campaign operating on a pay as you feel basis.

With the new French law coming into effect requiring supermarkets to deal with food waste more responsibly; I speak to Louiza about what she’s doing and her thoughts on the current food waste situation.

How did you become interested in the issue of food waste?

I had been experimenting with different ideas around ‘sustainable living’ for years, becoming increasingly aware of my own consumption and critical of consumer culture. Foraging for food in bins was just the next step on the journey! I became very interested in the creative form of eating with one another, whilst simultaneously exploring the use of artistic processes as a tool for socio-political change.

How do supermarkets react with your requests for their food waste?

I am yet to collect from the bigger supermarkets but I do collect from local stores, community events and food banks. Requests can be a bit of a shock at first. I think people fear judgement, so sometimes owners or staff lie to me claiming they have zero waste. Once, I had been asking for food from an organization that told me multiple times that they didn’t have waste. Out of the blue, I received a call one-day saying that my request had not left their mind and that they had come to terms with the fact that they do have waste. She asked if I could come in and pick up the surplus that she now believed to exist! It was an amazing, amazing moment for me. We’d planted an idea, and been patient. We’d built trust and challenged pre-existing fear/shame about waste. It really confirmed that there is so much potential when stores say no, as it’s the invisible thought processes that continue out of our control that will make positive impact.

What is Curb?

Curb is solely a food waste campaign. We have a business plan that works toward putting itself out of business.

Curb recently faced the issue of turning up to an event with cooked food and being told they couldn’t serve it. Does Curb face these kinds of obstacles often?

This was the first time that we’d turned up and been told we couldn’t serve our food. This was not because of health and safety, or because the food was once deemed ‘waste’ but because there was confusion within the organization of the festival. It is a real-life problem that caterers who are charging prices for food at festivals, are going to need to cover their overheads. The caterer was just upset and fearful of other people sharing food as she saw us as competition. We were very understanding, compromised a great deal, but we were not going to let our beautiful food go to waste!

How do you deal with the legality of serving out of date food?

I just do it. I think there are times when corporate law has its place, and there are times when it doesn’t. I feel the issue of food waste is because we don’t listen to common law. We are people of the planet and there is food that is safe to eat being wasted, due to profiteering, constructed policies and beauty ideals. The bottom line of Curb is to disrupt this. However, in order to acquire and rescue the most food from being wasted, I have to compromise with the system at the moment and make sure there is no reason why food businesses can say that they ‘can’t’ give us their surplus. I abide by everything we need to in order to push forward our campaign – but I’m always honest about the contradictions and make sure I share these kinds of dilemmas with people in conversations.

Do you think the new laws in France are useful and will they be effective?

I think that the use and effectiveness that will come out of them is essentially getting food waste onto public and political agenda. I don’t think it will make much difference to the reality of food waste, as laws are very easy to get around if you’re a big corporation that makes lots of money and works with the government.

I think it’s excellent as a first step, but I find it so problematic! Distributing food waste to charities and non-profits is actually just moving the responsibility to those in the third sector. This has been hugely devastating for decades and is never a solution! It merely removes moral, social, ethical and environmental conscience away from those systems and institutions that cause it and on top of that, it passes on the weight, time, cost and conscience to those working with extreme effort to combat their mistakes. We need to get to the root, but I appreciate this kind of legislative change (whether truly enforced or not) is definitely the first step in the right direction.

And finally, how can we make changes to food waste in the UK or even globally?

As a human race, I think we need to rediscover our connection with food. I believe that we are only so wasteful because we have little to no respect for food. We are completely blinded by a construction of what food is – hidden away from all parts of the food chain and only exposed to food as a commodity to buy/sell. Most of us only experience food at the Retail part of the system.

If we could disrupt this idea individually and on a society level, we would have so much more respect for food. We need to become conscious of what is on our plate, where it comes from, how it grows, what it does to sustain life, how much value it has and what it means to share food with others… then I don’t think we would create policies, legislation or practices that puts colossal amounts of good food to waste!

This is what Pay As You Feel is all about for me. This is why Curb exists.

A glimpse of art, shock and social engagement

Social issues are explored with all manner of approaches by a wide range of artists. It is a subject of much importance and endless debate. Santiago Sierra, Petr Pavlensky and Paul Harfleet.

Social issues are explored with all manner of approaches by a wide range of artists. It is a subject of much importance and endless debate. Santiago Sierra’s controversial work sparks strong reactions of anger and offense whilst others such as Rikrit Tiravanit use more subtle ways to address issues. This article looks at some of those who go beyond audiences’ expectations and shock thresholds to deliver some truly thought provoking and outrageous works.

A huge part of contemporary art practice concerns itself with social change. Many argue that the purpose of art is to engage people with such issues. Joseph Beuys term social sculpture views the whole of society as an artwork, to which all members can contribute. Beuys believed that art has the potential to transform society;

‘Art is the only political power, the only revolutionary power, the only evolutionary power, the only power to free humankind form all repression’. (Beuys, 1973)

Santiago Sierra. Image via Lisson Gallery website

10 INCH LINE SHAVED ON THE HEADS OF TWO JUNKIES WHO RECEIVED A SHOT OF HEROIN AS PAYMENT, 302 Fortaleza Street. San Juan de Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico, October 2000

DVD projection (4:3 ratio)

Santiago Sierra. Image via Lisson Gallery website

Santiago Sierra: Dedicated to the Workers and Unemployed

Installation view

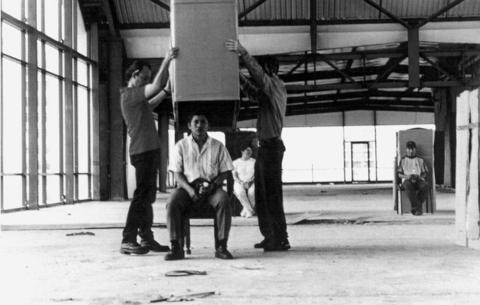

Santiago Sierra, «Laborers who cannot be payed, remunerated to remain in the interior of carton boxes», 2000

Eight people paid to remain inside cardboardboxes, 1999 | Courtesy: Galerie Peter Kilchmann, Zurich | Photography | © Santiago Sierra

Santiago Sierra’s work has criticized the institution of art. His work seemingly aims to expose capitalism by strongly critiquing its corporations’ unjust methods of production, confronting the audience by highlighting poor, unfair labour conditions and the extremities workers will endure by reproducing these same exploitative conditions, inflicted in the name of art. He has often employed underprivileged workers, prostitutes and drug addicts to perform pointless and laborious tasks, paying them the minimum amount possible to do so. He implicates the audience and attacks the desensitised numbness of the consumer who accepts the inevitable crimes that must take place in order for them to buy their commodity.

8 people paid to remain inside cardboard boxes would appear to unsuspecting audiences at first glance as minimalist sculptures, unaware of the excruciating labour, to which it refers. The worker here is put in a position of shame in which they have undignified conditions imposed upon them with no control over the work.

Sierra is criticised for always inflicting these conditions on others and not himself, however, considering his work aims to imitate the capitalist system, perhaps his role in this is to be the very system he excoriates. This reaction is not unexpected by the artist – when you put your name on the work it seems that you’re held responsible for the capitalist system itself.’ (Sierra 2004).

Image via ESCÁPIST(S)

Images via ESCÁPIST(S)

More recently, the Russian artist Petr Pavlensky is using his body as a performative means of highly political activism to oppose conditions implemented by the state, responding to escalating laws suppressing activism and banning the promotion of homosexuality

He was catapulted into the international public eye in 2013 after nailing his scrotum to the cobblestones in the Red Square, Moscow. After undressing and affixing himself, he continued to stare vacantly at his injury in the freezing temperatures. This figure represented someone of apathetic, disempowered political indifference. Pavlensky previously received attention by sewing his mouth shut in 2012 whilst holding a sign reading ‘Action of Pussy Riot was a replica of the famous action of Jesus Christ’. This form of silent protest is usually a passive statement, reaching people through the visual rather than volume but with the addition of self mutilation comes an aggressive passion and the spectacle is difficult to ignore.

Mutilating his body as a metaphor for the condition of the social body is performative but imposing himself on public places is an installation that the audience has no choice but to passively consume, and the police have to choice to participate in, perhaps even unwillingly collaborate in, adding a depth to the work.

Addressing social issues through participation is the underlying concept of Paul Harfleets Pansy Project, an installation based series of works as a reaction to homophobic abuse. The project was a response to daily abuse in the streets, in a country considering itself to be accepting of homosexuality and diversity.

Placing flowers is a ritual upheld to communicate an accident or tragic event. Harfleet used this tool to mark the damaging seriousness of abuse. With the pansy carrying the weight of the insult directed at effeminate men and using it as an instrument, it is a universal signal for passersby. Stark titles such as Fucking Faggot! add a jarring and sobering context to the seemingly delicate act and associated sorrow of planting flowers, exuding confrontation.

Images via The Pansy Project

The criticism of many of these bold works is the element of shock tactic. It is critiqued as a shallow tool used to attract attention, but to truly consider this as a criticism one must ask if it is effective. If the aim of these works is to bring about social change, this strategy does indeed utilise shock to reach its intended audience; the large general public who can enable the change it seeks. In a climate where art is so entrenched in politics and social engagement, it is often discussed whether it is the responsibility of artists to address social issues. Petr Pavlensky himself believes “an artist has no right not to take a stand”, but in many cases, whether an artist accepts responsibility or not, there comes a point when their works’ impact on society may well be out of their hands.